Proximity sensors are aptly named for their ability to detect objects in close proximity. They are not suitable for detecting objects across a room or on a conveyor belt. Their focus is on detecting objects up close and personal. Inductive proximity technology allows detection from physical contact with the sensor head to a few millimeters away. When choosing the right type of inductive proximity technology, several factors must be considered. Let’s start at the beginning.

Inductive proximity sensors may seem magical, but they operate based on specific magical characteristics. To prove my point, show them (and try to explain them) to a kid. Imagine an invisible electromagnetic field surrounding the sensors. This field can only be disrupted by a metal target. Different metals can affect this field at varying distances, depending on the type of metal and the sensor used. In simple terms, the sensor can detect if an object is a metal and, to some extent, the type of metal– all without touching the object physically.

Now that we’ve covered the basics, let’s focus on understanding the characteristics of the magical electromagnet field, its impact on sensing range, mounting, and the risks of sensor and/or part damage.

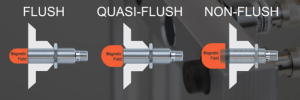

You may have heard the terms flush or non-flush used for inductive proximity sensors. I’ll throw one more into the mix: quasi-flush.

Non-flush mounting

Non-flush mount proximity sensors offer the longest range – the air gap between the target and the sensing head. This can be a good thing or a bad thing, depending on the situation. For precise positioning requirements, the extra range might cause issues. However, if precision is unnecessary, the extended ranges could be beneficial as objects might come into range slightly differently. One major downside of non-flush sensors is their susceptibility to damage. Typically, several millimeters to half an inch of the sensing head is exposed, increasing the risk of shearing off the sensor head or damaging the object you are detecting.

Flush mount proximity

With flush-mount proximity, you gain some protection for both the sensor head and the object being detected, but it comes with a trade-off of reduced sensing range. This is because the shape of the electromagnetic field coming out of the sensing head is focused to avoid triggering the mounting block or other hardware.

Quasi-flush mounting

If you are looking for a Goldilocks solution, consider quasi-flush mounting. With this style of sensing head, you recess the sensor into a mounting block, which helps focus the electromagnet field a bit more, thereby adding more field length compared to a flush mount. It is important to ensure your mounting block has a bevel around the sensing head to avoid false triggers of the output.

So, when deciding which type to use, I recommend using flush or quasi-flush sensors for any target that may come into contact with the sensing head. This choice will prolong the sensor’s life and better ensure proper target triggering. Non-flush sensors are great when you need a larger gap between the target and the sensing head, and precision is not a big issue.

In closing, proximity sensing is designed to be a non-contact form of object detection, specifically metal objects. The goal is to avoid any contact with the sensing head, although we’re aware that object/sensor collisions can happen.