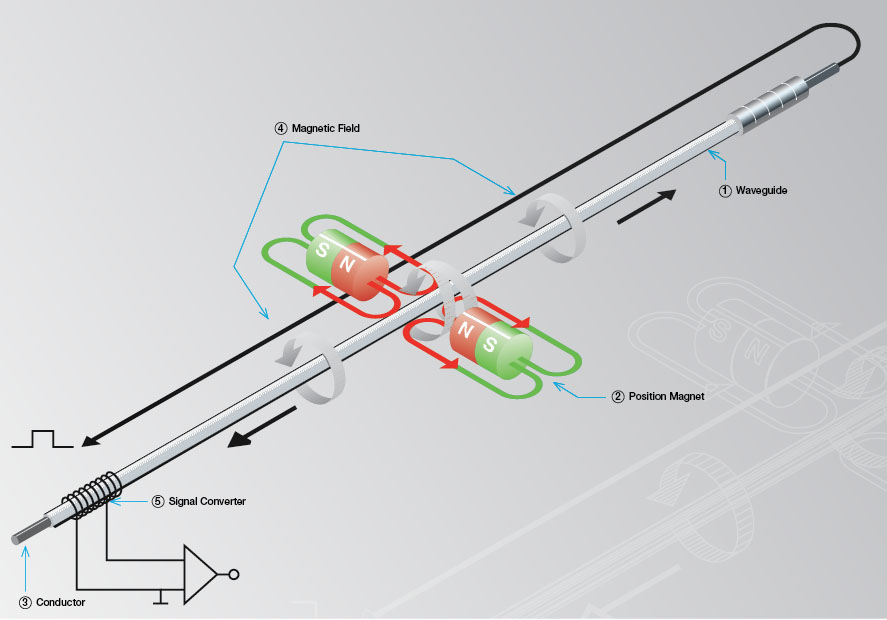

In a previous blog post, we looked at the basic operating principle of magnetostriction and how it is applied in a linear position transducer. In this post we’re going to take a more in-depth look at this popular sensing technique and the factors that can contribute to its usability in transducer applications.

As we’ve seen, the magnetostrictive effect is produced using a permanent magnet that is fixed either around or mounted some distance away from the ferromagnetic alloy that is being used. Now, if you’re like me and you’ve spent countless nights lying awake wondering how the effect of magnetostriction in a transducer is changed by the strength of the applied magnetic field and how that pertains to the output of a magnetostrictive transducer, then there isn’t need to look much further than this blog post. The strength of the magnetic field (which is directly related to distance through an inverse cubed relationship) projected onto the ferromagnetic material plays an incredibly critical role in the effect of magnetostriction. In Figure 1 you can see a depiction of the how the magnetostrictive effect varies at differing values of magnetic field strength.

Since magnetostriction does not behave perfectly linearly, some consideration must be taken into account when choosing a magnet and mounting system for your transducer. Potential problems occur if the magnet is mounted too far away from or too close to the transducer (thus producing either too much or too little magnetic field). But before we explore why too much or too little magnetic field is a problem, let’s compare it to the most desirable magnetic conditions.

Ideally, the goal is to choose a magnet and mounting distance which can produce a magnetic field that will fall within the green region from Figure 1. In this region, the magnetostrictive effect can be approximated as linear, thus being used to produce a strong and consistently predictable output response. As for what actual magnetic field strength values fall within this range, that is almost entirely dependent on the properties of the ferromagnetic alloy that you are using. In a standard application, for instance, one in which a magnet and transducer is fixed inside of a hydraulic cylinder where the magnet is mounted in a fixed position relative to the transducer rod (as shown in Figure 2.), this magnetic field value will not vary so there is no reason to worry about how the magnetostrictive response could vary. The device is designed to operate in Figure 1’s green region.

Problems can arise when dealing with externally mounted transducers in which the user has a significant amount more freedom in the selection of magnet and its mounting design. These instances could look incredibly different depending on the application. However, Figure 3 shows how this sort of design would come into play in a “floating” magnet application. At greater distances or when using weaker, non-standard magnets, the magnetic field will fall into the first red zone on Figure 1. In this region, the magnetic strength is too weak for a signal to be processed as an output by the transducer. This is primarily caused by the effect of magnetic hysteresis which is essentially a “charge up” zone and creates an exponential relationship in this zone, rather than the desired linear relationship. On the other hand, if you attempt to use a strong, rare-earth magnet too close to the transducer, it will produce too strong of a magnetic field and move beyond the green region into the second red zone. The problem here is that the magnetostriction will saturate and can potentially cause output loss. Also, similarly to the weaker magnetic field strength, the behavior cannot be approximated using the same linear relationship that we see in the green zone of Figure 1. As with the green region of the graph, the magnetic field strength values that lie in the red zones are dependent on the properties of the material as well as the response processing electronics of the transducer.

Due to these issues, there are many things to consider if you’re using an externally mounted transducer and choosing a non-standard mounting method in your application. You need to be careful when mounting a magnet too far away or using a rare-earth magnet too close to the transducer.

For more information visit www.balluff.us.